Osteoporosis Resources for Primary Care: Identification

What should our priorities be in Primary Care?

Identification, follow-up and long-term management

In November 2017 the ROS published Quality Standards for Osteoporosis and Prevention of Fragility Fractures to reflect and encourage good practice for all services, including primary care, involved in the fragility fracture prevention pathway.

Primary Care plays a key role in:

- Identifying people at risk of fragility fracture and carrying out the appropriate assessments;

- Providing follow-up support to patients;

- Supporting the long-term management of osteoporosis with the patient and their carers.

Brief information on the elements of the standards particularly relevant to Primary Care is given below. For full details, please refer to the standards.

Standard 1: Identifying people at risk of fragility fractures

- Adults aged ≥50 years with a new fragility fracture are systematically and proactively identified

- Adults aged ≥50 years with a vertebral fracture are systematically and proactively identified

- Adults with co-morbidities or taking drug therapies commonly associated with increased fracture risk are identified

- Adults aged ≥65 years with a history of two or more falls in the past year are identified

Standard 2: Assessing fracture risk

- Investigations to assess risks of fragility fractures and falls are offered to adults identified by the fracture prevention pathway – for example, fracture risk assessment using FRAX or QFracture, Quality-assured axial DXA within 12 weeks from referral, relevant laboratory and imaging investigations to clarify diagnosis and inform treatment decisions

Standard 3: Information and support

- Adults are offered relevant information and engaged in discussion and decisions made to agree their care plan

Standard 4: Interventions to reduce fracture risk

- Adults at high risk of fragility fracture are offered appropriate drug treatment within 5 weeks of assessment and are given information about how to take the drug treatment

Adults at high risk of falling are referred to falls prevention services

Standard 5: Follow-up and long-term management

- Adults who are recommended a drug treatment for osteoporosis are asked about adverse effects and adherence to treatment, and a long-term treatment review is carried out

Standard 6: Reducing pain and functional impairment after fracture

- Adults who have a fragility fracture are offered interventions to reduce pain and functional impairment

Download the full standards: Quality Standards for Osteoporosis and Prevention of Fragility Fractures

Further information:

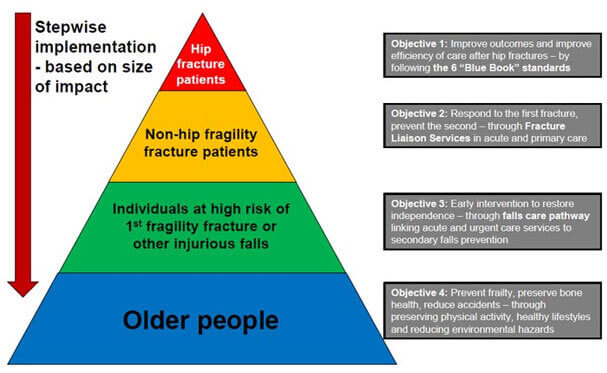

The Department of Health in England has produced commissioning guidance for the NHS in the Falls and fractures section of the Prevention Package for Older People. The key objectives illustrated in the pyramid below provide GPs and service commissioners with a stepwise implementation plan, based on the size of the impact, from a clinical and cost-effectiveness standpoint.

In 2017, NICE published Quality Standard [QS149] Osteoporosis. The standard contains four quality statements: Assessment of fragility fracture risk; starting drug treatment; adverse effects and adherence to treatment; long-term follow up.

In Scotland, health professionals should follow the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidance: Management of Osteoporosis and the Prevention of Fragility Fractures (142) and Management of Hip Fracture in Older People (111).

What is the role of a Fracture Liaison Service (FLS)?

Fracture Liaison Services

A Fracture Liaison Service (FLS) is a system aiming to ensure that fracture risk assessment (and treatment where appropriate) is delivered to all patients with fragility fractures. An FLS usually comprises a dedicated case worker (often a Clinical Nurse Specialist) who works to pre-agreed protocols to case-find and assess fracture patients. An FLS can be based in Primary or Secondary Care and requires support from a medically qualified practitioner, be they a GP with specialist interest or a hospital doctor with expertise in fragility fracture prevention. In 2010, 37% of localities in England, Wales and Northern Ireland had an FLS, whilst Scotland has almost universal coverage.

Where an FLS is established at the local hospital, this service can ensure that patients presenting with new fragility fractures receive the assessment they need immediately post-fracture. In some localities, a Primary-Care-based FLS has been established that operates by the Nurse Specialist providing a peripatetic service to local general practices to case-find prior fragility fracture patients and those at high risk of first fracture. Both approaches have been shown to close the care gap routinely evident in localities lacking an FLS. The National Audit of Falls and Bone Health in Older People 2010 provides information regarding access to FLSs by area.

Where an FLS is already in place, this service will help to support practices to achieve the quality of care required to meet osteoporosis Quality and Outcomes Framework indicators.

The ROS has FLS Clinical Standards that provide the core standards that every FLS should meet to ensure that correct identification, investigation, information, intervention and integration with Primary Care are achieved, within a framework of quality, to the long-term benefit of fracture patients – the 5IQ approach.

By adopting these standards, evidence-based best practices can be replicated effectively across the UK to reduce the burden of fractures while improving outcomes for patients and ensuring appropriate use of National Health Service (NHS) resources.

What are the risk factors for fragility fracture?

The most important risk factors for fragility fracture are:

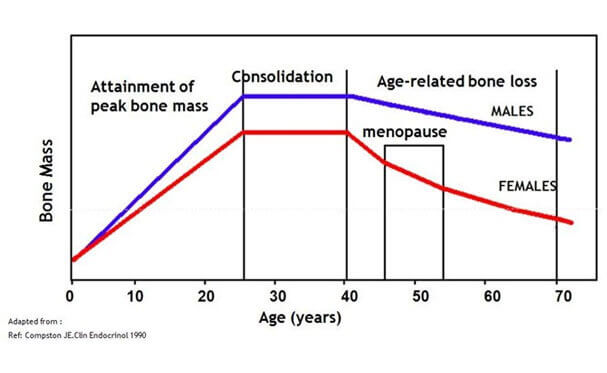

- Age: Incidence of fragility fractures increases with age and peak incidence occurs between the ages of 60 and 75 years, with vertebral fractures peaking in the over 70s and hip fractures peaking in the over 80s

- Gender: Fragility fractures are twice as common in women as in men

- Low bone mineral density (BMD): Risk of fracture increases progressively with reduction in BMD. Every 1 SD reduction in BMD equates approximately to a doubling of the relative risk of fracture. The majority of fragility fractures occur in those with a BMD T-score above the osteoporosis threshold of 2.5 or less (i.e. within the osteopenic range) rather than those with osteoporosis (i.e. with a T-score of ≤ −2.5). This is attributable to the population of patients with osteopenia being more numerous than those with osteoporosis and the osteopenic range covering a broad spectrum of fracture risk

- Parental history of hip fracture: Maternal and paternal history of hip fracture is the most reliable indicator of genetic risk of fragility fracture

- Low body mass index (BMI): BMI of ≤ 19 kg/m2 is associated with an increase in the risk of hip fracture (and probably other fractures) in both women and men

- Hormones: Premature menopause (in women under the age of 45) – whether natural or induced by surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy or endocrine therapy - increases risk. Risk is increased in men who have had orchidectomy or androgen-deprivation therapy

- Medical conditions associated with bone loss: These include rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease (e.g. Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis), malabsorption (e.g. coeliac disease, pancreatic insufficiency), cystic fibrosis, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, vitamin D insufficiency, immobilisation (e.g. resulting from CVA or Parkinson's disease), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus type 1 and chronic renal or hepatic disease.

- Drug treatments associated with bone loss: These include oral corticosteroids, aromatase inhibitors, androgen deprivation therapy, some anti-epileptic medications and glitazones

- Lifestyle factors: Alcohol intake ≥ 3 units per day, smoking, recreational drug use and immobility increase fracture risk

- Falls: Non-vertebral fragility fractures usually result from a fall in an individual with compromised bone strength; thus, the risk factors for falls should be routinely considered in older patients, as advocated by NICE guidance

- Prior fragility fracture: Good evidence exists to support GPs investigating patients with a low trauma fracture, particularly those of the wrist, spine, humerus or hip. Patients who have sustained a recent fracture are at increased risk of sustaining another fracture, irrespective of site and such fractures can often indicate the beginning of a cascade of fractures culminating in hip fracture, with all its implications. For individuals sustaining a new incident fracture, risk of further fracture increases 5-fold in the first year, during which nearly a quarter of the re-fractures occur. Just over half of re-fractures will occur over the 5 years following the presenting fracture and risk persists for 15 years

Search

Search

Login

Login