Epidemiology of Osteoporotic Fracture: an overview

By Fiona Kirkham-Wilson1 and Elaine Dennison2

1Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

2MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Centre Southampton

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a disease of reduced bone mineral density and changes to the microstructure of bone causing a weakening and associated increased risk of fracture. Women are at higher risk of sustaining a fragility fracture than men, in part due to the impact of menopause on bone mineral density (BMD). These osteoporotic fractures have an associated increased morbidity while hip and vertebral fractures also increase mortality risk up to 5 years post-fracture. It is also clear that as the population ages, the incidence of osteoporosis and resultant fractures is increasing, although this is not evenly distributed across the globe. In particular co-morbidities and lifestyle factors contribute significantly to the risk of developing osteoporosis – addressing these factors presents an opportunity to reduce the incidence of fracture.

Definition of osteoporosis

Although the definition of osteoporosis has traditionally used a BMD threshold of more than 2.5 standard deviations (SD) below the young, adult mean [1], it does not include the micro-architectural changes independent of BMD which contribute to the increased risk of fracture. More recently clinicians have moved to assessing an individual’s 5- or 10-year absolute risk of an osteoporotic fracture [2] through algorithm-based screening tools to better define and treat those with or at risk from osteoporosis, such as FRAX.

Definition of osteoporotic fracture

A fragility fracture is defined as one that occurs after only moderate trauma (equivalent to a fall from standing height or less). The areas of fracture are typically in bones with higher levels of the spongy trabecular bone which is far more porous than compact bone formed of harder osteons. Trabecular bone is found in the ends of long bones, vertebrae, and the flat bones of the axial skeleton, such as the pelvis. This explains the typical distribution of osteoporotic fractures, which are more common in women and rates increase exponentially with age.

Incidence and prevalence

As the global population ages the incidence of disease associated with the ageing process increases, as is the case for osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. In 2018 the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) estimated that there are 16 million women and 4 million men living with osteoporosis across the 6 European Countries included: France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom [3]. In the UK it is estimated that one in two women and one in five men aged over 50 will have an osteoporotic fracture in their lifetime [4]. A diagnosis of osteoporosis increases the risk of fracture, but there are many other contributing factors to absolute risk including co-morbidities, sex and fracture site. All osteoporotic fractures have an associated increased in morbidity, but hip and vertebral fractures show a clear association with increased mortality up to 5 years following the fracture in both sexes. Distal forearm fractures have been associated with a slight excess mortality in men only [5 ].

Hip fracture

Rates of hip fracture rise exponentially from age 50 with a 2:1 ratio between women and men. Temperate climates, such as the UK, see a seasonal variation in the rates of fracture, with winter contributing the most fractures, although most of these injuries occur indoors.

In the UK survival rates for the 12 months following hip fracture are considerably lower than expected rates – 63.3% observed versus 90.0% expected for men and 74.9% observed versus 91.1% expected for women [4]. Pre-fracture health status contributes to this 12-month mortality risk, with the immediate post-fracture period being the most perilous, however, the elevated risk of death remains for up to 10 years post hip fracture.

Hip fractures have the highest morbidity of any fracture, with immediate post-fracture complications such as pneumonia being common. Around half of those who sustain a hip fracture, having previously been independently mobile, will require assistance following the injury. As age increases, so too does the risk of becoming dependent following a comparable injury in a younger person.

Join the ROS as a professional member to read the full article and similar expert content

References

[1] Geneva WH. Study group on assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. InTechnical Report Series 1994. World Health Organization.

[2] Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Dawson A, De Laet C, Jonsson BJ. Ten year probabilities of osteoporotic fractures according to BMD and diagnostic thresholds. Osteoporosis International. 2001 Dec;12(12):989-95.

[3] Kanis J, McCloskey E, Harvey NC, Javaid MK, Borgstrom F. Broken bones, broken lives: a roadmap to solve the fragility fracture crisis in the United Kingdom

[4] Van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HA, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone. 2001 Dec 1;29(6):517-22.

[5] Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, Jacobsen SJ, O’Fallon WM, Melton III LJ. Population-based study of survival after osteoporotic fractures. American journal of epidemiology. 1993 May 1;137(9):1001-5.

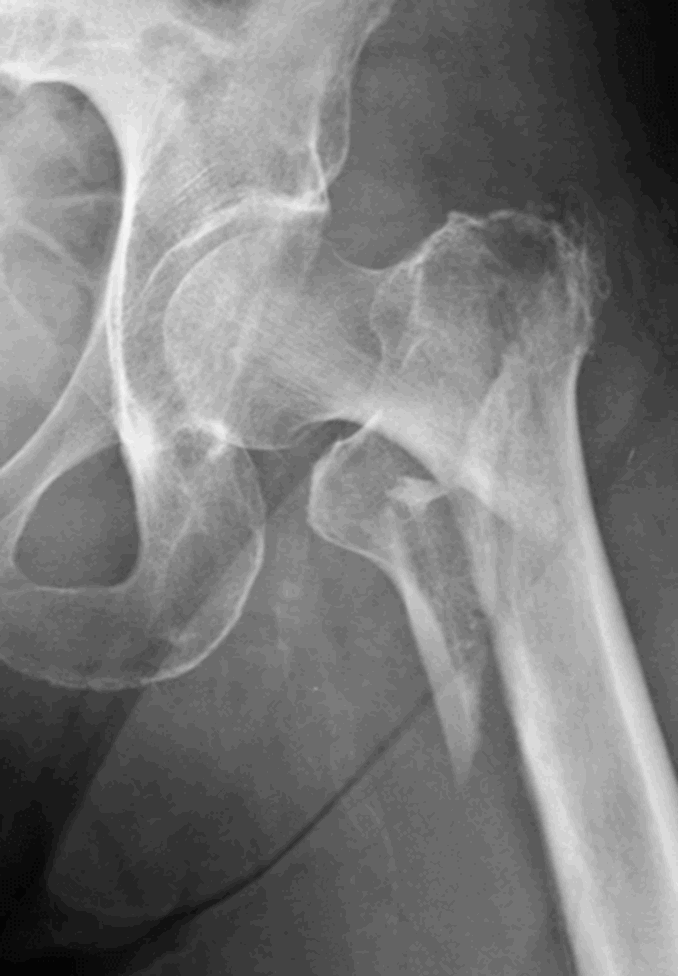

Radiograph of an intertrochanteric

hip fracture

Search

Search

Login

Login